Blue Jay Nest

Spring brings us warm weather, a reawakening of perennial plants, and the most interesting and entertaining bird behavior. Over the next few months, you can witness all aspects of bird life – courting a mate, nest building, laying and incubating eggs, feeding hatchlings and fledglings as they venture out on their own. Providing nesting sites and nesting boxes will help to bring this experience to your backyard.

Courtship takes a variety of forms. Woodpeckers drum to attract a partner and establish their territory. They peck rapidly on trees, downspouts, your house, or any surface which will produce the desired sound – the louder the better. Other birds use songs to attract a mate. A male with a larger repertoire may be considered more attractive. Waterfowl bob their heads and flutter their wings to attract mates. Mourning doves and mockingbirds fluff out their feathers and dance. Blue jay and cardinal males offer their female partners a seed as a gift of affection.

Robin Nest

Understanding the nesting behavior of a particular bird species and providing the habitat they prefer will increase the likelihood of them moving into your neighborhood. Birds that build open, cup-shaped nests are called open-cup nesters. Cardinals and Robins are examples. Ground-nesting birds build their nests on the ground by constructing an open-cup nest or creating a shallow depression in the earth, sand or leaf litter. Birds that nest in cavities of trees, man-made structures or nesting boxes are called cavity-nesters.

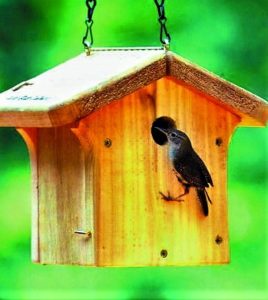

Wren Using Nesting Box

While birds prefer natural sites, cavity-nesting birds will willingly accept man-made nesting boxes placed in the right habitat. Examples of species that readily use properly located and appropriately built nesting boxes include wrens, chickadees, titmice, nuthatches, bluebirds, woodpeckers, purple martins, kestrels, owls and wood ducks.

When the nestlings are large and strong enough, they leave the nest. In most cases the parents still protect and feed the fledglings until they become self-sufficient. During this time, the young can be quite susceptible to predators. Often, fledgling birds spend quite a bit of time on the ground while they are learning to fly. However, most young birds do not need to be ‘rescued.’ And rescuing them may disrupt the natural course of events.

Chipping Sparrow Nest

If you find a baby bird that you believe to be orphaned, you will need to determine if the bird is truly orphaned before you intervene. The best way to make this determination is to watch for at least two to three hours (from a concealed location) for the return of a parent. If the baby is not in danger from predators, it is best to leave it on the ground. If the fledgling is in danger, try to locate the nest and return the baby to it. It is not true that a bird will reject a baby that has been touched by humans.

If you determine that the baby is truly orphaned, call a wildlife rehabilitator. Having a native songbird in your possession without an appropriate license is illegal. In the meantime, keep the baby warm and physically supported in a makeshift nest (e.g. plastic berry box lined with paper towels) and follow any instructions given to you by the rehabilitator.

Once their first brood of young has been raised, many species will nest a second time. In some seasons, species such as robins, cardinals, bluebirds and mourning doves may raise three or more broods. With the right habitat, you may be entertained all summer long by avian families.